|

DOI: 10.7256/1339-3057.2016.1.17387

Received:

24-12-2015

Published:

27-04-2016

Abstract:

In this work the author compares the research of conscious action in the context of the Vygotsky and Luria theory, and modern research on executive function. With few exceptions the modern research in the West conceptualizes the notion of “executive function” independently from its original meaning established by Vygotsky and Luria, and in an ever increasing manner is being viewed as a function, or directly governed by neuronal processes taking place in the brain, or as a complex, “context-free” cognitive construct. But such approach towards willful behavior is contradicted by empirically established facts: high dependency of the level of willfulness of behavior experienced from the content of instruction and from culture in which the research is conducted. The scientific novelty of this research is substantiated by the fact that this work is first to compare the approach of Vygotsky and Luria on conscious action with the modern concept of executive action based on experimental research and practical work with children.

Keywords:

Style of communication, Comparative analysis, Speech, Creativity, Willful behavior, Child development, Executive function, Conscious action, Luria, Vygotsky

Executive function: the concept Executive function (EF) is a complex cognitive construct that, according to some researchers, features three principal components: working memory, inhibitory control and attention flexibility [1][2]. Executive function has been increasingly recognized as a construct that is of central importance to cognitive development. It is also viewed as key to understanding special phenomena such as perseverations [3][4]. Deficits in EF are linked to a variety of disorders such as autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) [5][6], attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [7][8][9], phenylketonuria [10] and learning difficulties [7][11]. There is a fair amount of evidence demonstrating that improvements in children’s executive performance positively affect their understanding of "theory of mind", compliance with social rules, rule-based reasoning and other related cognitive achievements [1][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19]. More importantly, inhibitory control and attention shifting are reliable predictors of early academic abilities such as mathematics and literacy [19][20][21][22][23]. Cognitive interpretation of EF in current research and the problem of context-sensitivity In contemporary research EF is predominantly viewed and studied as a domain-general, context-free cognitive function that is directly linked to the maturation and functioning of certain areas in the brain, mainly the prefrontal cortex (PFC) [1][24][25][26][27][28][29]. For example, a classic EF test in psychology is the Wisconsin Card Sort Test (WCST) [30]. In this test, participants are presented with a series of target cards that vary in different dimensions (shape, color, and number). After having sorted the cards on one of the dimensions (e.g., shape), the participants are asked to sort the cards again on another dimension (e.g., colour). Patients with lesions in the prefrontal cortex typically perseverate on this task, continuing to sort by the initial dimension [86]. In a children’s version of the card-sorting task, children are asked to sort a series of coloured shapes, first by one dimension (e.g., colour) and then by another (e.g., shape). Whereas 3-year-olds systematically perseverate on the pre-switch rules during the post-switch phase, 5-year-olds switch quickly [4][31]. According to the cognitive complexity and control theory (CCC theory), age-related changes in executive functioning can be measured by “age-related changes in the maximum complexity of rules that children can formulate and use when solving problems” [4, p.111].

However, as research data on EF performance across various conditions, ages and cultures accumulated, it became increasingly evident that cognitive accounts of EF run into problems. One of these problems was a discovery that children's performance on EF tasks is highly sensitive to extraneous factors. For example, it was shown that performance on the rule-switching task often improved significantly with only slight adjustments to the instructions (i.e., when the task’s rules were spelled out in a less instructive manner, or when the task was to sort abstract figures rather than recognizable shapes) [32]. Variability in children’s EF performance across different contexts is particularly evident in studies targeting distortions of inhibitory control in learning [33].

Another challenge to cognitive accounts such as CCC theory is explaining cross-cultural variability in children’s performance on EF tasks. Thus, it has been shown that in Confucian cultures, such as China and Korea, preschoolers show a better performance on a number of EF tasks when compared with their Western peers [12] [18][34]. Some researchers suggest that these differences can be attributed to differences in teaching and parenting styles between East and West, with Asian practices placing a stronger emphasis on self-control in children than Western practices [18][35]. It appears that the development of EF in children can slow down or accelerate under the impact of social factors such as a parenting style.

The aforementioned experimental data suggest that EF is inherently unstable and vulnerable to situational influences. This creates a problem for cognitive accounts of EF because vulnerability to extraneous factors is not characteristic of a typical domain general cognitive construct. One of such typical cognitive constructs is object permanence. Object permanence is the understanding that objects continue to exist even when they cannot be observed (seen, heard, touched, smelled or sensed in any other way). Research has shown that object permanence is highly robust across cultures and even species. Indeed, object permanence, which is directly linked to PFC development, is not only stable cross-culturally [36], but is acquired similarly by typically developing children and children with intellectual disabilities, such as Down syndrome [37][38][39]. It should be noted that children with Down syndrome suffer diminished performance on a number of EF tasks, compared with non-Down syndrome disabled participants [40]. Object permanence has been confirmed to also exist in monkeys and other animal species [41][42][43][44][45].

The realization of these problems led researchers to distinguishing between hot and cool EF. Whereas cool EF is required in order to solve abstract decontextualized tasks, hot EF function is necessary in order to cope with the tasks that involve affect and motivation [46][47]. On top of that, cool EF is associated with dorsolateral regions of the PFC whereas hot EF is associated with the ventral and medial PFC regions. The distinction between hot and cool EF, though useful, does not solve the context sensitivity problem because both cool and hot versions of EF, albeit to a different extent, show sensitivity towards contextual factors. In addition, as some authors commented, “it seems likely that measures of EF always require a combination of hot and cool EF … and, hence, that the difference between hot and cool EF is always a matter of degree” [48, p.617]. Vygotsky-Luria’s conceptualization of EF as “conscious action” The aforementioned difficulties with cognitive accounts of EF make one search for alternative theoretical accounts. One such alternative account belongs to Vygotsky, who coined the concept of “conscious action” -- an action that includes purposeful planning and voluntary (verbally mediated) control. As Vygotsky puts it, “ When refracted through the prism of thought, action is transformed into a different action, which is now conscious and thereby voluntary and free…” [49, p.250]. The concept of conscious action, which was also used by Luria, was an early prototype of the current concept of EF. Vygotsky described the development of conscious action as children’s growing capacity to use their intelligence to control their “affects” (needs, emotions, impulsive tendencies). For instance, in one of Vygotsky’s experiments, it was shown that changing the personal significance for children of a certain task (by upgrading the task from a task the children had to perform to a task they were supposed to train other children to perform) improved their executive performance. Inspired by their new role as instructors, the children were able to resume their performance on a monotonous task that they had previously abandoned because of tiredness [ibid, pp. 252-253].

Elaborating on Vygotsky’s concept of conscious action, Luria depicted it as a natural consequence of interactive activities. Conscious action first appears when 10- to 12-month-old children learn to obey simple commands from adults (e.g., to pick up a toy). Later, the children become able to perform purposeful actions on their own by giving themselves verbal commands [50][51]. At the same time, in his neuropsychological studies, Luria linked conscious action to the PFC [52]. As a result, two alternative ways of interpreting conscious action were made possible: (1) conscious action as a context-dependent social skill derived from interactive activities and (2) conscious action as a context-free cognitive construct governed by the PFC. Although the first interpretation retained its significance in Russian psychology, it was the second interpretation that came to the forefront of research within the current explosion of studies and theory on EF [12][13][14][53][1][54][55][15][56][34][2][32].

With a few exceptions [58], contemporary research has increasingly portrayed EF as a complex context-free cognitive construct governed by neural mechanisms in the brain [1][2][4][57]. It is only recently that the role of social context in children’s cognitive development started coming to the forefront of theory and research, predominantly around children’s social understanding and the effect that such understanding can have on executive functioning [59][60]. Thus, in a recent edited book on EF and social understanding, the following key questions have been raised: Does social interaction play a role in the development of executive function or, more generally, self-regulation? If so, what forms of social interaction facilitate the development of executive function? Do different patterns of interpersonal experience differentially affect the development of self-regulation and social understanding? [61]. In the chapter entitled “Vygotsky, Luria and the Social Brain”, a comparison is made between Vygotsky-Luria’s approach towards EF and current approaches. The chapter points out that contemporary accounts of EF have paid only scant attention to Vygotsky-Luria’s account. The chapter argues that the latter can add useful insights to our understanding of the linkages between executive functioning and social understanding because both executive functioning and social understanding are higher mental functions developmentally structured by social experience and therefore they should interact with each other.

Nevertheless, the chapter leaves open the question of exactly how the modern cognitive accounts of EF can benefit from Vygotsky-Luria’s approach, and the empirical basis of this chapter remains strictly within the cognitive approach to EF. For instance, the chapter refers to recent studies showing that language plays an important role in self-regulation [62][63] and that a child’s rate of production of noncommunicative utterances (i.e., “egocentric speech”, as Piaget and Vygotsky originally called such utterances) is positively related to the child’s concurrent performance on a classic EF task (the Tower of London) [64][65]. These studies provide useful illustrations of Vygotsky’s point regarding the regulative role of speech for action as well as of Vygotsky & colleagues’ earlier experiments showing that the production of egocentric utterances increases when a problem-solving process is disturbed or becomes more difficult [66, p.48-50]. Yet these studies do not answer the question of why Vygotsky-Luria’s original understanding of EF as conscious action should be brought back from oblivion. Emphasising Vygotsky’s point that EF is a semiotically mediated higher mental function does not answer this question too, because modern cognitive concepts of EF also include semiotic mediation, e.g., in the form of children’s intelligent application of rules in problem solving [4]. Other chapters of this volume examine the evidence which shows that children’s advance on EF is necessary for improving their social understanding, such as their grasp of "theory of mind". The volume also contains a comprehensive analysis of social and cognitive factors that affect the development of EF. Yet, this analysis leaves many problems unresolved. One of these problems is the problem of irreducible diversity in theoretical definitions of EF. Another problem is the presence of puzzling incongruities in research data regarding which extraneous factors correlate with EF and which do not. In order to minimize these incongruities, the authors suggest narrowing the concept of EF down and linking it to a specific range of tasks and contexts. This suggestion only emphasises the key feature embedded in the cognitive approach toward EF: the tendency to represent EF as a domain-general construct. Viewed in this way, EF is either completely free from social context, or linked to a very specific and limited context.

As the aforementioned edited book demonstrates, even turning to the original work by Vygotsky and Luria does not necessarily help theorists to resolve the problems raised by the cognitive interpretation of EF, because the original work has to be read in translation, which sometimes distorts or obscures its true meaning. However, the true meaning of Vygotsky-Luria’s interpretation of EF as conscious action is essentially quite simple: EF is inherently social and context embedded.

Accordingly, one of my aims in this paper is to reinstate the original Vygotsky-Luria's model of EF as conscious action. Another aim is to evaluate this model's potential for theory and research on EF, as well as for applications of this research in educational practices. Finally, my aim is to compare Vygotsky-Luria's model with the contemporary cognitive model of EF, by evaluating strenghts and weaknesses of both models.

Vygotsky-Luria’s original model of EF and its potential for theory, research and educational applications Essentially, Vygotsky-Luria's model presents EF as a skill of “tool-assisted” self-regulation derived from interactive activities. Further in this paper I will refer to this model as "Tool-Assisted Model", or TAM for short. Two empirically verifiable conclusions follow from TAM: (1) children’s performance on EF tasks should be highly sensitive to contextual influences, and (2) children's executive performance should benefit from using psychological tools. These psychological tools can vary from strictly cognitive (i.e., loud verbal self-commands that precede and assist an action) to social (i.e., presenting a child with a model for emulation) and to affective-emotional (i.e., altering personal significance of a task for a child by changing the child’s social position in the adult-child interaction). Using studies of EF based on TAM, I am going to assess an extent to which TAM can explain the phenomena that the cognitive approach to EF struggles to explain: (a) children’s tendency to instantaneously improve or worsen their EF performance after small changes in contextual components of a task and (b) cross-cultural differences in children’s performance on identical EF tasks.

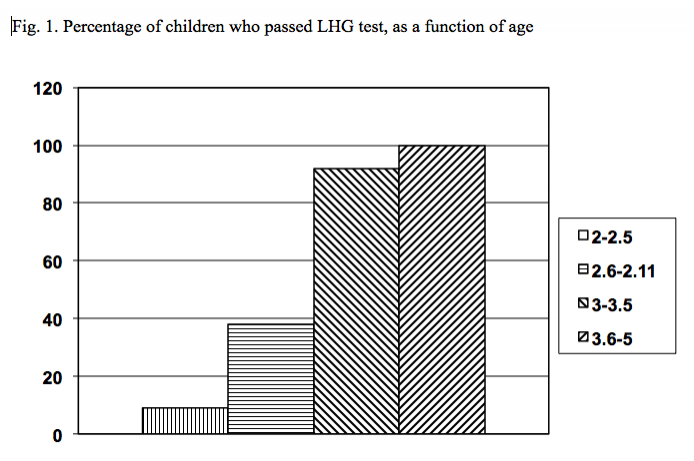

For an illustration of the first empirically verifiable implication of TAM (high sensitivity to social contextual influences), I am going to consider studies on a modified version of Luria’s hand game task (LHG), conducted with 2- to 5-year-old children [67][68]. In this task, in the pre-test condition, a participant and an experimenter had a set of two identical toys (i.e., a small flag and a rattle). The child was asked to lift his or her flag (a reaction) whenever the experimenter lifted his rattle (a stimulus) and lift his or her rattle after the experimenter lifted his flag. Children were first trained on this task and then, after passing the criterion of 5 successive actions without a failure, given a test trial of 15 stimuli in random order. Taken as a percentage, the ratio of imitative actions to the total number of actions in the test trial yields a score (imitation score, IS) assessing the child’s success or failure at inhibiting the impulse to make imitative actions. Essentially, IS is a measure of the effectiveness with which children are able to use their EF to control their actions. Children were considered to pass the test if their IS was less than 20%. The results indicated that the ceiling effect on this task was reached at the age of approximately 4 years (see Fig. 1).

Children who successfully passed the test were offered a more difficult version of this task, which put the task in a new social context. In this version of the task a partner (the child’s peer or an adult) joined the performance. The partner was sitting opposite to the child, with the experimenter sitting to one side (see Fig. 2). Unbeknownst to the child, the partner (who was the experimenter's confederate) was asked to randomly make right or wrong responses. In this situation, if the partner’s action was incorrect, then the implicit confusion that the LHG inherently contained was added to by the partner’s wrong action. The combined confusing impact made on the child by the experimenter's stimulus and the partner's wrong response will be referred to as "confusing social pointing", or CSP for short.

Fig. 2. Performing LHG under the condition of confusing social pointing

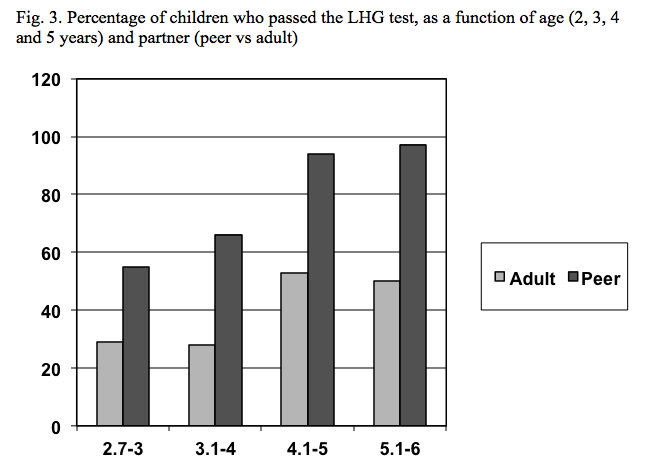

This confusing impact puts an increased load on EF and impedes the child’s performance. The task was presented in two versions: children were asked to perform LHG together with a confederate (action test) and to verbally assess the confederate’s actions (verbal test). The results indicated that the children’s performance on the task was severely impeded by CSP. Interestingly, the cause that obstructed the children’s ability to effectively employ EF was not of a cognitive nature. As can be seen from Fig. 3, in children older than 5 years, the confusing social stimuli coming from a peer partner had little effect on their performance. However, when similar stimuli were generated by an adult partner,

more than 50% of the children failed the test and started copying the partner’s incorrect actions. Interestingly, on the verbal version of the test most children effortlessly told the adult partner's incorrect actions from the correct ones. This shows that children’s inability to effectively employ EF in the adult-partner CSP condition was caused not by deficits in their cognitive functions (such as knowledge of programs, memory or critical thinking) but by an emotional factor: the children perceived the adult partner as an infallible model for emulation and imitated the partner’s incorrect actions, even though they realised that these actions were wrong.

I suggest that this emotional attitude towards adults as infallible models for emulation is a result of the young children's typical position in their social interactions with adults. Due to a considerable gap that initially exists between cognitive abilities of young children and those of adults, in their social interactions with adults young children usually take a subordinate position of a "learner", whereas adults enjoy the dominant position of a "teacher". As years go, the children get used to this inequality of social roles, and develop the emotional attitude towards adults as infallible models for emulation. If this assumption is true, then replacing this emotional attitude with a more critical attitude toward adults as individuals who are vulnerable to doubts and errors can only be accomplished by changing the child's subordinate position in his or her interactions with adults for a position of an "equal partner', or, better still, for a position of a "leader". There is ample literature on how cognitive semiotic artefacts such as signs, symbols, texts, formulae, and language, enhance executive functioning in children [69][70][71][72][73], yet the issue of what kind of non-cognitive semiotic tools can be used to affect executive functioning has been explored to a significantly lesser extent. I suggest that altering children’s roles in their social interactions with adults is one of this kind of tools.

The above theoretical considerations resulted in the study, which illustrates the second implication of TAM -- sensitivity of EF performance to cross-cultural differences. In this study, three alternative intervention conditions were run on children whose performance on LHG had been adversely affected by CSP [67][68].

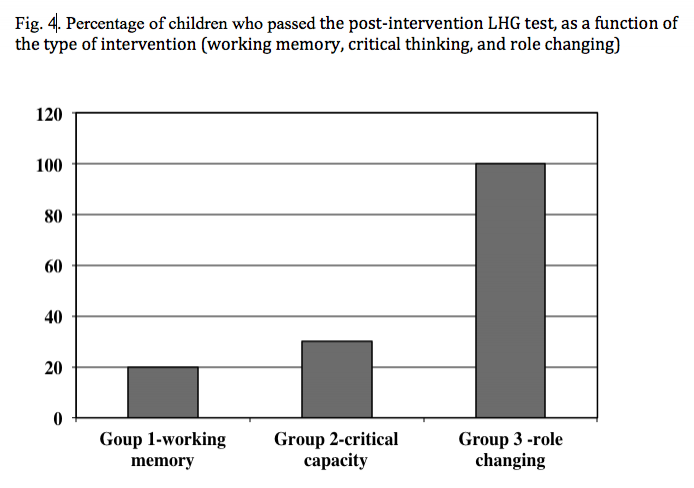

In a pre-intervention trial, children’s performance on LHG was tested in the child-partner and adult-partner conditions. Only children who passed the test in the child-partner condition but failed in the adult-partner condition participated in the intervention and post-intervention trials. Children were randomly divided in three groups. Each of these groups was subjected to a special intervention treatment. In Group 1, intervention involved consolidating the program in children’s working memory: additional intensive training on the program was given to each child. In Group 2, intervention involved facilitating children’s critical thinking: verbal discussion of the partner’s actions was encouraged until the children were able to effortlessly notice and verbally report to the experimenter all of the partner’s incorrect actions. In both of the above groups, the children’s role in their interaction with adults, and a personal significance of the task for the children, was that of “being a pupil”—the one who is supposed to follow the adult’s instructions, not to give instructions to adults. In contrast, in Group 3 children were given a leading role in the social interaction: they were encouraged to teach the “naïve” adult to correctly perform the task. This change in roles alters the personal significance of the task for the child from “being a pupil” to “being a teacher”. After each intervention trial, a post-intervention trial was run in which the children performed LHG with the same adult partner who had participated in the pre-intervention and intervention trials. Results of the post-intervention trials indicated that training children on working memory and critical thinking (Groups 1 and 2) restored the effective use of EF in only 20 to 30% of the children, whereas changing the social role (Group 3) allowed all of the children to effortlessly pass the post-intervention trial (Fig. 4). The success of training in Group 3 supported the assumption that giving the child a leading role in his of her interactions with an adult eliminated the child’s attitude towards the adult partner as an infallible model for emulation. Eliminating this emotional attitude toward an adult enhances the child's ability to resist CSP and allows the child to employ his or her critical thinking more effectively than before. Altogether, the results of these experiments showed that children’s ability to effectively employ their EF could be impeded by social impacts, such as confusing social pointing; yet this ability can be restored through using a non-semiotic psychological tool—upgrading the child’s role in the adult-child interaction from the role of "a pupil" to that of "a teacher".

With their roles upgraded, children develop a new image of the adult-partner: the image of a person who, like the children themselves, can experience vacillations, hesitations and doubts and can make errors on tasks that are familiar to the children. It is possible that the age at which children develop this new image of adults varies cross-culturally. For instance, some studies have shown that in Asian cultures, in which children are encouraged to help adults in their domestic work and care for siblings, the children surpass their Western peers on prosocial behaviours (for a review, see [85]). Similarly, one can assume that working together on simple tasks, children and adults in Asian cultures often interact on equal terms and the children's attitude toward adults as infallible models for emulation disappears at an earlier age than in children of Western cultures. Indeed, in Western cultures children’s participation in adults’ activities is encouraged to a lesser extent than in Asian cultures and the image of an adult as an infallible model for emulation can therefore last longer.

The above studies aimed to illustrate sensitivity of EF to social contextual factors. In order to illustrate EF's sensitivity to cognitive contextual factors I am going to refer to the study in which a version of Luria’s pattern-making task was employed [51][74][75][76]. In this task, a participant is presented with a patterned strip of blue and red tokens and instructed as follows: “See, it makes a pattern: blue-red, blue-red”). The participant is then asked to continue making the pattern, taking tokens from the pile of tokens available next to him or her. This task allows for a quantifiable assessment of changes in executive performance caused by changing cognitive contextual factors, such as a structural complexity of the pattern. For instance, a participant who coped with a symmetrical pattern (blue-red, blue-red) can later be given a more complex asymmetrical pattern (blue-blue-red, blue-blue-red) to perform.

Another cognitive factor that can affect participant’s ability to effectively employ their EF on the pattern-making task is increasing the difficulty of the task’s motor component. To increase the difficulty of the motor component, instead of making patterned rows from tokens, participants are asked to produce the same patterned rows with a pencil, by drawing geometrical figures (a circle and a cross). This makes the motor component more complicated because drawing geometrical figures requires children to master their hand and finger motions, which for young children is significantly more difficult than the task of moving tokens from one place to another. It was assumed that increasing the difficulty of the motor component would shift part of the performers’ attention from maintaining patterns to creating individual elements of the patterns. This shift of attention can have a detrimental effect on executive performance by increasing the load on the two components of EF—attention flexibility and inhibitory control—without significantly increasing the load on working memory at the same time.

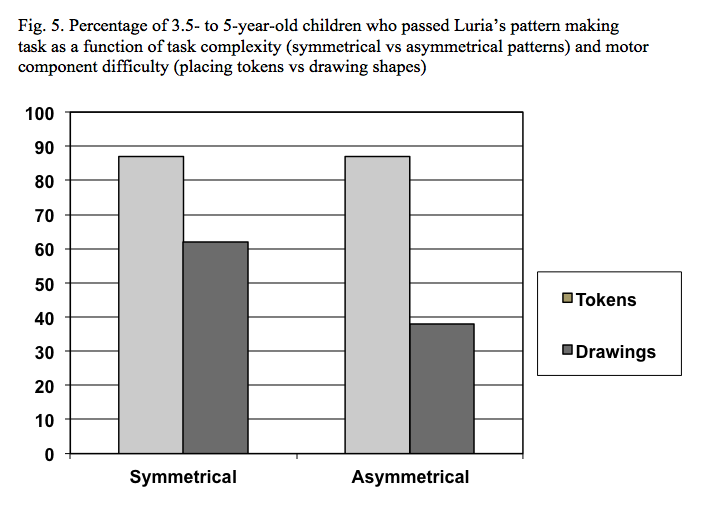

The results supported this prediction. As Fig. 5 shows, for 3.5- to 5-year-old children, on both levels of the task’s structural complexity (symmetrical and asymmetrical), increasing the difficulty of the motor component (changing from moving tokens to drawing figures) significantly decreased the number of children able to cope with the task.

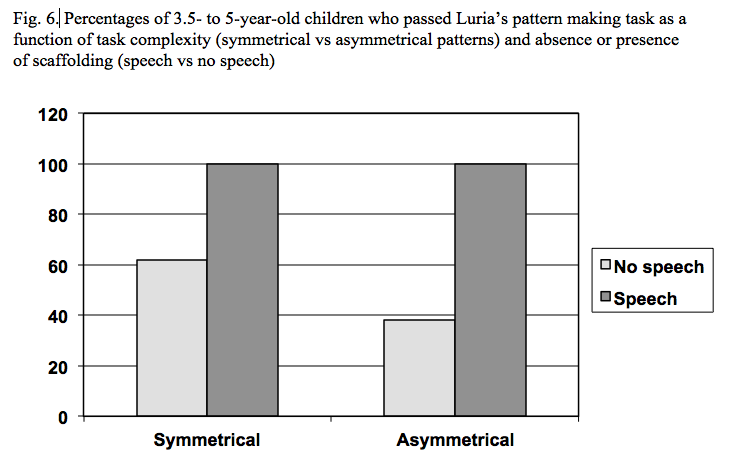

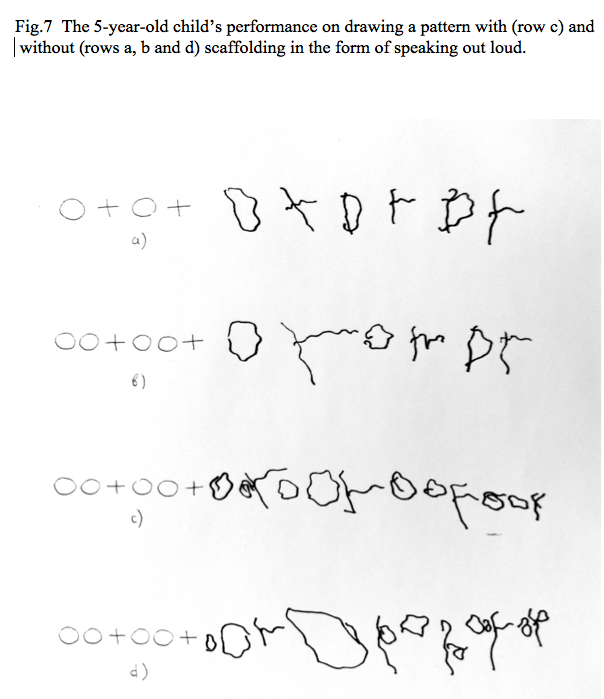

One more cognitive contextual factor that can affect performance, positively in this case, is “educational scaffolding”. Usually, scaffolding means using a certain psychological tool with the aim to help children cope with the task [77][78]. In this study, scaffolding was given in the form of speaking out loud each element of the pattern before actually implementing the action. Specifically, the child was encouraged first to say out loud what action he or she was going to make (i.e., “I am going to pick a black token”, or “I am going to draw a cross”) and only after that execute the action. As Fig. 6 shows, adding scaffolding in the form of verbal planning allowed all of 3.5- to 5-year-old children in this experiment to successfully perform programs consisting of both symmetrical and asymmetrical patterns. Fig. 7 illustrates the patterns drawn by a 5-year-old child with and without scaffolding: the child copes with the symmetrical pattern without scaffolding (row a) but fails to produce the asymmetrical pattern and begins to perseverate (row b). When scaffolding is given by asking the child to announce her actions

before implementing them, the child copes with the asymmetrical pattern (row c) but switches back to a symmetrical pattern as soon as scaffolding was taken off (row d). All of the aforementioned examples show that children’s ability to engage their EF, viewed from the TAM perspective, is highly sensitive to social and cognitive contexts.

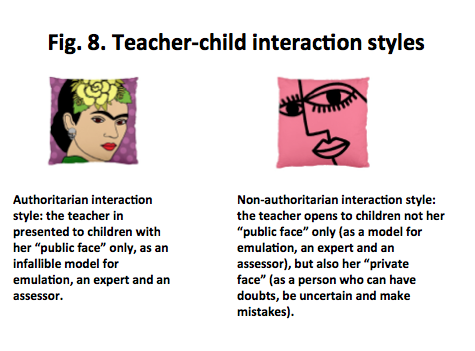

Finally, as I already mentioned, TAM implies the possibility of using affective-emotional psychological tools in order to improve children’s effective use of EF in a classroom setting. One of such tools is changing social interaction style between a teacher and his or her students (“interaction style” for short). Interaction style is a relation of two interacting individuals A and B to power. Under the “authoritarian interaction style” power belongs to one individual only. Person A has the right to teach and control Person B, and Person B doesn’t have the right to teach and control person A. In contrast, under the “non-authoritarian interaction style” power is equally distributed between both parties. Both Person A and Person B have equal rights to teach and control each other (see Fig. 8)

In a series of studies, changing the adult-child interaction style was used to improve children’s performance on the LHG task [68][79]. Younger (3-4 years) and older (4-5 years) experimental groups in a Moscow preschool centre were compared with control groups of children of the same age in another preschool. In the experimental groups, the children’s social roles in their interactions with adults were changed to fit the profile of the non-authoritarian interaction style, by providing the children with the opportunity to systematically correct each other’s and the adults’ mistakes. In the experimental groups, two adults participated in each lesson. One adult played the role of an instructor (AI) and the other played the role of a “child” (AC). The AI gave instructions to the whole group on how to perform the tasks while the AC sat among the children and performed the tasks as though he or she were a child, making the same typical mistakes that children often make on these tasks. After instructing the class and giving the children time to learn and implement the task, the AI asked each child to publicly display what he or she had accomplished, while encouraging other children to critically assess the child’s production. In due course, the AC was asked to display his or her product to the class, and the children were given an opportunity to assess and correct the adult’s work. In this way, the children in the experimental groups were given the opportunity to both absorb the curriculum from the AI and act as assessors of each other’s and the AC’s performances at the same time. Any authoritarian disciplinary measures (i.e., verbal threats to punish the children, harsh voice intonations and unwelcoming facial expressions) were not allowed.

In this approach, an adult was presented to children in more than one “social dimension”: as an expert and authority figure (the AI) and as a person, who can have doubts, make errors and fail on tasks (the AC). In the course of the program, the AC and the AI swapped roles every two weeks.

In the control groups, the traditional for preschools in Russia authoritarian interaction style was left untouched. There was only one teacher, who performed the roles of an instructor and an assessor. Children did not have the right of arguing with a teacher or criticizing her actions. If children misbehaved, disciplinary measures were applied (i.e., scolding or ousting out of the classroom). The children were not encouraged to assess and criticize each other’s actions and products. Care was taken that experimental and control groups were taught the same curriculum throughout the experiment.

The program was run for 5 months and incorporated more than a hundred lessons on math, storytelling, drawing, modelling and other activities. In the course of the program, in experimental groups 5 stages were observed in children’s attitude towards the non-authoritarian interaction style. In Stage 1, the children were perplexed and puzzled. In Stage 2, the children often laughed at the AC and were over critical towards her actions, often naming the AC’s correct actions as incorrect. In Stage 3, the children started spontaneously correcting each other actions. In Stage 4, the children started getting used to the new style. Mocking the AC and hypercriticism has ceased. Finally, in Stage 5, the evening of the critical activity was taking place. The children who used to be passive in the beginning of the program started to be more active at criticising each other’s and the AC’s actions.

There were also dynamical changes in children’s perception of the AC. In Stage 1, children were curious, but also showed cautiousness and alienation. Most children looked at the AC with interest but did not approach her or spoke to her. In Stage 2, children fell apart in 3 groups. Some children became hostile and aggressive towards the AC, often threatened to punish her (the "hostile” group). Other children were positive but didn’t show much interest in communication with the AC (the “neutral” group). There were also children who “fell in love” with the AC, clung to her, told her their most secret thoughts and feelings (the “loving” group). In the end of the program (Stage 3) part of the children moved from the “hostile” and the “neutral” groups to the “loving” group.

One more effect that is worth noting was a crash of discipline in the experimental groups in the beginning of the program. Sensing that they are no longer restrained, some children started going around the classroom during the lessons, speaking loudly, disturbing other children and interrupting the AI. However, by the middle of the program (i.e., in about 2.5 months after the start) discipline was restored, which shows that discipline during lessons does not necessarily require a support from the authoritarian type control. Nevertheless, restoring discipline under the non-authoritarian interaction style does require from adults some patience and tolerance toward naughty children - the price that is well worth paying for the achieved results.

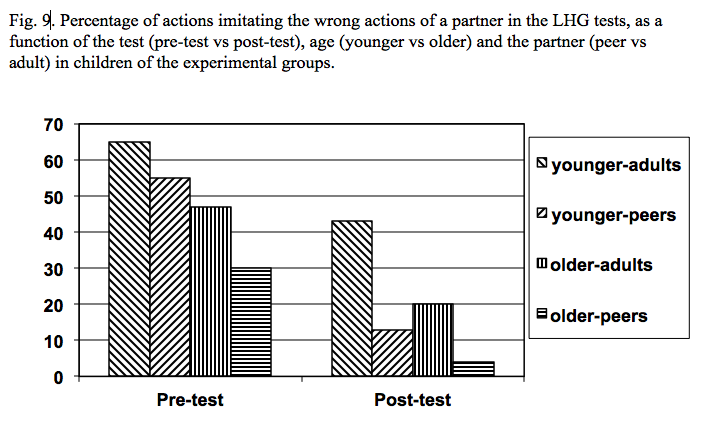

Before and after the program, the children were given four versions of the LHG test. As Fig. 9 shows, in the experimental groups, both younger and older children showed a significant decrease in the percentage of imitations of the partner’s wrong actions (and, therefore, a significant increase in their ability to effectively employ EF). In the control groups, there was no decrease in children's tendency to imitate the partner's incorrect actions.

In the end of the program, we also measured the children’s spontaneous creativity on two kinds of lessons: drawing and sculpturing. Spontaneous creativity is the children's tendency to add something of their own to a model that was given to them by a teacher to emulate (see Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. The model for emulation and the actual child's drawing

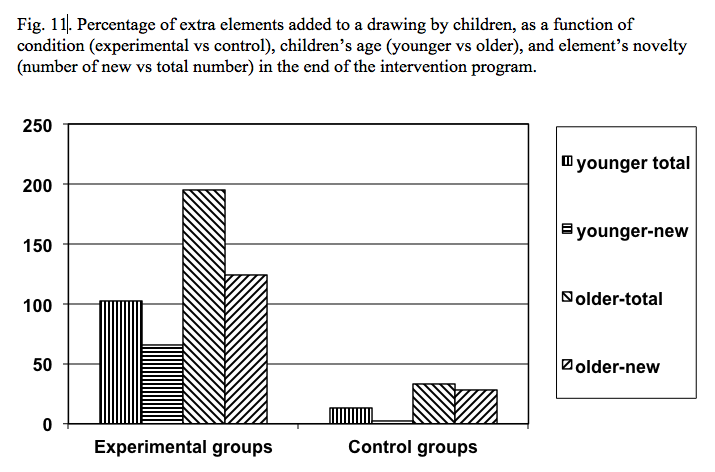

Interestingly, the children’s progress in their ability to employ EF was accompanied by an increasing number of extra elements that the children added to a model given to them by the AI during the drawing lessons. As Fig. 11 shows, the percentage of new extra elements and the percentage of the total number of extra elements added by a child to his or her drawing in the experimental groups were significantly larger than in the control groups.

One might ask why the children's tendency to be creative in their drawings positively relates to their ability of effectively employing their EF. One possible answer is that creativity at lessons in young children requires the ability to inhibit a tendency to strictly imitate models that are given by adults—the tendency that is often encouraged by adults. As a result, the increase in children’s ability to resist the tendency to imitate adults’ actions (i.e., to effectively employ their EF during performance) can release the children’s natural inclination toward bringing diversity and variability in their performance. Another possibility is that the general climate of freedom of judgment and behaviour that builds up when children are given the opportunity to act as critical assessors of adults’ actions might give the children the tacit message that being creative is OK. It is also possible that both of the aforementioned factors contributed to the observed phenomenon of increased creativity in the children in the experimental groups.

As the studies reviewed above have shown, TAM can provide answers to certain questions brought up by the cognitive approach towards EF. TAM can also be used to develop psychological tools (both cognitive and non-cognitive) capable of enhancing children’s ability to employ their EF in performance on tasks that require self-regulation. Interestingly, in the recent years, the idea of using scaffolding to correct diminished EF in children with various disabilities (such as ADHD and ASD) has become widely accepted in practice, especially in the US. Thus, many studies that do not mention Vygotsky-Luria’s approach nevertheless consider the role that verbal instruction, teaching children various ways of self-government and self-control, family assistance and other forms of scaffolding play in promoting children’s ability to engage their EF in learning and problem solving [6][11].

At the same time, just like the cognitive accounts of EF, TAM has its limitations: it only works in regard to children (patients) who possess an integrated system of higher mental functions and have intact intelligence. Particularly important is the child’s (patient’s) ability to plan and regulate their actions either internally or by speaking out loud. When this link between speech and action is absent or disturbed, the effectiveness of TAM for correcting the child’s ability to employ his or her EF is low. For instance, the aforementioned study of children’s performance on Luria’s pattern-making task showed that introducing scaffolding to children younger than 2 years of age failed to improve their performance: while speaking aloud the correct action (i.e., “put in the black token after the white one”), the children perseverated in their actual behavioural performance by making one-colour rows of white tokens without consulting the given pattern. Even children aged 2 to 2.7 years, in which the coordination between speech and action has already progressed to a considerable extent, were capable of using this coordination only in regard to simple symmetrical patterns; when a more complex asymmetrical pattern was offered, scaffolding failed to help the children follow the pattern [67]. A similar limitation of TAM showed up in studies on children with retarded intelligence. In these studies, conducted by Luria's colleagues and students Khomskaya, Martsinkovskaya and Lubovsky, two groups of children participated. The children of Group 1 (with the so-called cerebro-asthenic syndrome) enjoyed a well-coordinated system of higher mental functions and intact intelligence but, because of brain tissue intoxication, suffered some distortions in mental functioning, such as lack of flexibility in mental processes. When performing tasks that challenged their EF, they used to tire quickly and had a tendency of switching to uncontrolled impulsive actions. In contrast, the children of Group 2 (mental retardation, oligophreny) were able to work for a much longer time but had impeded coordination between language and action. In one of these studies, children were asked to press a bar each time a red light was turned on but refrain from pressing the bar when a blue light was on. After the base level of performance was assessed in a pre-test, scaffolding was introduced: on seeing the light, the children were required to first say out loud the action that they were going to do (i.e., «should press the bar») and only afterward proceed with the action. The children of Group 1, who showed a command of their actions through speaking aloud, also showed significantly improved performance when scaffolding was added. However, this did not happen with the children of Group 2, whose coordination between speech and language was disturbed because of their retarded intelligence. Either these children were unable to correctly speak aloud the required action (i.e., they kept repeating the same verbal command, «should press», independently of the light's colour) or their actions did not follow their verbal commands [16][50][80]. These studies have confirmed the results of Vygotsky's experiments, discussed earlier, which showed that changing personal significance of the task for children restores performance in typically developing children but fails to do so in mentally retarded children [49]. Current researchers in education studies also note that integration between children's cognitive functions and their motor skills is a necessary condition for correcting the children's disabled EF (for a review, see [7]). Conclusion The reviewed studies suggest that Vygotsky-Luria’s original model of executive functioning as conscious action (TAM) is immune to the problems unresolved by the current cognitive accounts of EF (such as the problem of high sensitivity of executive performance on typical EF tasks to extraneous factors). TAM can also be used to develop helpful psychological strategies for improving executive performance in typically and atypically developing children, both individually and in a classroom. At the same time, this model is best suited to individuals who possess a well-integrated system of higher mental functions (such as language and intellectually guided actions). When such integration is underdeveloped or disturbed, the cognitive models of EF, which link EF to maturation and functioning of PFC, can show a more effective path towards correction or enhancement of executive functioning, in particular, through carefully tested and measured pharmacological interventions [81][82][83][84]. One can therefore conclude that the cognitive models of EF, oriented towards neurochemical intervention in correcting executive performance, and TAM, which emphasizes the use of higher mental functions for such correction, rather than being alternatives, mutually complement each other. Only the analysis of specific cases of disturbed or diminished EF and the patterns of integration (or the absence of integration) between EF and intelligence, language, memory and other mental functions can help decide which of the existing models of EF (and the interventions recommended by these models) fits these cases best.

References

1. Hughes, C. (1998). Executive function in preschoolers: Links with theory of mind and verbal ability. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 16, 233–253.

2. Welsh, M.C., Pennington, B.F., & Groisser, D.B. (1991). A normative developmental study of executive function: A window on prefrontal function in children. Developmental Neuropsychology, 7, 131-149.

3. Brooks, P.J., Hanauer, J.B., Padowska, B., & Rosman, H. (2003). The role of selective attention in preschooler’s rule use in a novel dimensional card sort. Cognitive Development, 18, 195-215.

4. Zelazo, P. D., Muller, U., Frye, D., & Marcovitch, S. (2003). The development of executive function in early childhood. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 68(3), Serial No. 274.

5. Hughes, C., Russell, J., & Robbins, T. W. (1994). Evidence for executive dysfunction in autism. Neuropsychologia, 32, 477–492.

6. Ozonoff, S., & Schetter, P.L. (2007). Executuve disfunction in Autism Spectrum Disorders: From research to practice. In L. Meltzer (Ed.), Executive Function in Education. From theory to practice (pp. 133-160). New York: The Guilford Press.

7. Denckla, M.B. (2007). Executive function: Binding together the definitions of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder abd Learning Disavilities. In L. Meltzer (Ed.), Executive Function in Education. From theory to practice (pp. 5-18). New York: The Guilford Press.

8. Sergeant. J. (2000). The cognitive-energetic model: an empirical approach to Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 24, 7–12.

9. Simeonsson, R.J., & Rosenthal, S.L. (Eds.) (2001). Psychological and developmental assessment: Children with disabilities and chronic conditions. New York: Guilford Publications Inc.

10. Diamond, A., Prevor, M., Callender, G., & Druin, D. P. (1997). Prefrontal cortex cognitive deficits in children treated early and continuously for PKU. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 62(4), Serial No. 252.

11. Meltzer, L., & Krishnan, K. (2007). Executive function difficulties and learning disabilities: Understandings and misunderstandings. In L. Meltzer (Ed.), Executive Function in Education. From theory to practice (pp. 77-107). New York: The Guilford Press.

12. Benson, J.E., & Sabbagh, M.A. (2010). Theory of mind and executive functioning: A developmental neuropsychological approach. In Zelazo, P.D., Chandler, M., & Crone, E., (Eds), Developmental social cognitive neuroscience (pp. 63-80). New York: Psychology Press.

13. Carlson, S.M., Moses, L.J., & Hix, H.R. (1988). The role of inhibitory processes in young children’s difficulties with deception and false belief. Child Development, 69, 3, 672-691.

14. Cepeda, N.J., Kramer, A.F., & Gonzalez de Sather, J.S.M. (2001). Changes in executive control across life span: Examination of task-switching performance. Developmental Psychology, 37, 5, 715-730.

15. Kochanska, G., Murray, K., Jacques, T.Y, Koenig, A.L., & Vandergeest, K.A. (1996). Inhibitory control in young children and its role in emerging internalization. Child Development, 67, 490-507.

16. Luria, A.R. (1981) The development of the role of speech in mental processes: The regulative function of speech and its development. In Luria, A.R. (Edited by J.V.Wertsch) “Language and cognition”, Washington: V.H.Winston & Sons

17. Moses, L.J. (2001) Executive accounts of Theory-of-Mind development. Child Development, 72, 3, 688-690.

18. Oh, S., & Lewis, C. (2008). Korean Preschoolers’ advanced inhibitory control and its relation to other executive skills and mental state understanding. Child Development, 1, 80-99.

19. Sabbagh, M.A., Moses, L.J., & Shiverick, S. (2006). Executive functioning and preschoolers’ understanding of false beliphotographs, and false signs. Child Development, 4, 1034-1049.

20. Blair, C. & Razza, R.P. (2007). Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Development, 78, 647-663.

21. Gaskins, I.W., Satlow, E. & Pressley, M. (2007). Executive control of reading comprehension in the elementary school. In L. Meltzer (Ed.), Executive Function in Education. From theory to practice (pp. 194-215). New York: The Guilford Press.

22. Graham, S., Harris, K.R. & Olinghouse, N. (2007). Addressing executive function problems in writing: An example from the Self-Regulated Strategy development model. In L. Meltzer (Ed.), Executive Function in Education. From theory to practice (pp. 216-235). New York: The Guilford Press.

23. Roditi, B.N., & Steinberg, J. (2007). The strategic math classroom: Executive function process and mathematics learning. In L. Meltzer (Ed.), Executive Function in Education. From theory to practice (pp. 237-260). New York: The Guilford Press.

24. Bialystok, E., & Martin, M. (2003). Notation to symbol: Development in children’s understanding of print. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 86, 223–243.

25. Deák, G.O. (2000). The growth of flexible problem solving: Preschool children use changing verbal cues to infer multiple word meanings. Journal of Cognition and Development,1, 157–191.

26. Denckla, M. B., & Reiss, A. L. (1997). Prefrontal-subcortical circuits in developmental disorders. In N. A. Krasnegor, G. R. Lyon, & P. S. Goldman-Rakic (Eds.), Development of the prefrontal cortex: Evolution, neurobiology, and behavior (pp. 283–293). Baltimore: Brookes.

27. Perner, J., & Lang, B. (1999). Development of theory of mind and cognitive control. Trends in Cognitive Science, 3, 337–344.

28. O’Sullivan, L. P., Mitchell, L. L., & Daehler, M. W. (2001). Representation and perseveration: Influences on young children’s representational insight. Journal of Cognition and Development, 2, 339–365.

29. Zelazo, P. D., Carter, A., Reznick, J. S., & Frye, D. (1997). Early development of executive function: A problem-solving framework. Review of General Psychology, 1, 198–226.

30. Grant, D. A., & Berg, E. (1948). A behavioral analysis of degree of reinforcement and ease of shifting to new responses in Weigl-type card-sorting problem. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38, 404–411.

31. Frye, D., Zelazo, P. D., & Palfai, T. (1995). Theory of mind and rule-based reasoning. Cognitive Development, 10, 483–527.

32. Yerys, B.E. & Munakata, Y. (2006). When labels hurt but novelty helps: Children’s perseveration and flexibility in a card-sorting task. Child Development, 77, 15-89-1607.

33. Bernstein, J.H., & Waber, D.P. (2007). Executive capacities from a developmental perspective. In L. Meltzer (Ed.), Executive Function in Education. From theory to practice. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 39-54.

34. Sabbagh, M., Xu, F., Carlson, S.M., Moses, L.J., & Lee, K. (2006). The development of executive functioning and theory of mind: A comparison of Chinese and U.S. preschoolers. Psychological Science, 17, 74-81.

35. Kwon, Y.I. (2002). Western influences in Korean preschool education. International Educational Journal, 3, 153-164.

36. Dansen, P., & Heron, A. (2012). Cross-cultural tests of Piaget’s theory. Available onhttp://www.scribd.com/doc/18313664/Cross-Cultural-Tests-of-Piagets-Theory

37. Bruce, S., & Zayyad, M. (2009). The Development of Object Permanence in Children with Intellectual Disability, Physical Disability, Autism, and Blindness. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 56, 229-246.

38. Kahn, J. V. (1976). Utility of the Uzgiris and Hunt Scales of Sensorimotor Development with Severely and Profoundly Retarded Children. American Journal of Mental Deficiency 6, 663–665.

39. Wright, I., Lewis, V., & Collis, G.M. (June 2006). Imitation and Representational Development in Young Children with Down Syndrome. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 24, 429–450.

40. Rowe, J., Lavender, A., & Turk, V. (2006). Cognitive executive function in Down's syndrome. British Journal odf Clinical Psychology, 45, 5-17.

41. Churchland, M.M., Chou, I.H., & Lisberger, S.G. (2003). Evidence for object permanence in the smooth-pursuit eye movements of monkeys". Journal of Neurophysiology, 90, 2205–18.

42. Diamond, A., & Goldman-Rakic, P. (1989). Comparison of human infants and rhesus monkeys on Piaget’s AB task: Evidence for dependence on dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Experimental Brain Research, 74, 24–40.

43. Doré, F.Y. (1986). Object permanence in adult cats (Felis catus). Journal of Comparative Psychology, 100, 340–347.

44. Hoffmann, A., Rüttler, V., & Nieder, A. (2011). Ontogeny of object permanenand object tracking in the carrion crow, corvus corone. Animal Behaviour, 82, 359-367.

45. Miller, H., Cassie D. G, Vaughan A., Rayburn-Reeves, R., & Zentall, T.R. (2009). Object permanence in dogs: Invisible displacement in a rotation task. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16, 150–155.

46. Prencipe, A., & Zelazo, P. D. (2005). Development of affective decision-making for self and other: Evi-dence for the integration of first-and third-person perspectives. Psychological Science, 16, 501–505.

47. Zelazo, P. D., & Müller, U. (2002). Executive function in typical and atypical development. In U.Goswami (Ed.), Handbook of childhood cognitive development (pp. 445–469). Oxford: Blackwell.

48. Hongwanishkul, D., Happaney, K.R., Lee, W.S.C., & Zelazo, P.H. (2005). Assessment of hot and cool executive function in young children: Age-related changes and individual differences. Developmental Neuropsychology, 28, 617-644.

49. Vygotsky, L.S. (1983). The problem of mental retardation. In Vygotsky, L.S. Collected works. Vol.5, p.231-256. Moscow: Pedagogica (First published in 1935).

50. Luria, A.R. (1970). Human brain and psychological processes. Moscow: Pedagogica.

51. Luria, A.R., & Subbotsky, E.V. (1978). Zur fruhen Ontogeneze der steuerden Funktion der Sprache Die Psychologie des 20 Jahrhunderts. Zurich: KinderVerlag. 1978. 1032–1048.

52. Luria, A.R. (1980). Higher cortical functions in man. New York: Basic books.

53. Feldman, R. (2009). The development of regulatory functions from birth to 5 years: Insights from premature infants. Child Development, 2, 544-561.

54. Kochanska, G., & Aksan, N. (1995). Mother-child mutually positive affect, the quality of child compliance to requests and prohibitions, and maternal control as correlates of early internalization. Child Development, 66, 236-254.

55. Kochanska, G., Aksan, N., & Koenig, A.L. (1995). A longitudinal study of the roots of preschoolers’ conscience: Committed compliance and emerging internalization. Child Development, 66, 1752-1769.

56. Perner, J., Lang, B., & Kloo, D. (2002) Theory of mind and self-control: More than a common problem of inhibition. Child Development, 73, 3, 752-767.

57. Welsh, M.C., & Pennington, B.F. (1988). Assessing frontal lobe functioning in children: Views from developmental psychology. Developmental Neuropsychology, 4, 199-230.

58. Russell, J. (1996). Agency: Its role in mental development. Hove, UK: Erlbaum.

59. Carpendale, J. I. M., & Lewis, C. (2004). Constructing an understanding of mind: The development of children's social understanding within social interaction. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27, 79-151.

60. Carpendale, J. I. M., & Lewis, C. (2006). How children develop social understanding. New York: Wiley Blackwell.

61. Sokol, B., Muller, U., Carpendale, J., Young, A., & Iarocci, G. (2010). Self-and Social-Regulation: Exploring the Relations Between Social Interaction, Social Understanding, and the Development of Executive Functions. Published by Oxford Scholarship Online: http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195327694.001.0001/acprof-9780195327694

62. Winsler, A., Diaz, R. M., McCarthy, E. M., Atencio, D. J., & Adams Chabay, L. (1999). Mother-child interaction, private speech, and task performance in preschool children with behavior problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40, 891–904.

63. Winsler, A., Fernyhough, C., & Montero, I. (2009). Private speech, executive functioning, and the development of verbal self-regulation Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

64. Fernyhough, C., & Fradley, E. (2005). Private speech on an executive task:Relations with task difficulty and task performance. Cognitive Development, 20, 103–120.

65. Al-Namlah, A. S., Fernyhough, C., & Meins, E. (2006). Sociocultural influences on the development of verbal mediation: Private speech and phonological recoding in Saudi Arabian and British samples. Developmental Psychology, 42, 117–131.

66. Vygotsky, L. S. (1982). Thought and Language. In Vygotsky, L.S. Collected works. Vol. 2. Moscow: Pedagogica (First published in 1956).

67. Subbotsky, E.V. (1976). Psychology of partnership relations in preschoolers. Moscow: Moscow University Publ.

68. Subbotsky, E.V. (1993). The birth of personality. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

69. Bodrova, E. & Leong, D. (1996). Tools of the mind: the Vygotskian approach to early childhood education. New York: Merill.

70. Engeström, Y. (2007). Putting Vygotsky to work: The Change Laboratory as an application of double stimulation. In H. Daniels, M. Cole & J. V. Wertsch (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to Vygotsky. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

71. Frawley, W. (1997). Vygotsky and cognitive science: language and the unification of the social and computational mind. Harward, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press.

72. Kozulin, A. (2001). Psychological Tools: A Sociocultural Approach to Education. Harvard, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press.

73. Wertsch, J. (1991). Voices of the Mind: Sociocultural Approach to Mediated Action. Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press.

74. Luria, A.R., & Subbotsky, E.V. (1972a). Studies on the development of conscious action. Report 3. New Studies in Psychology and Physiology of Age (Novye Issledovaniya v Psikhologii i Vozrastnoi Fiziologii), 2, 22-27.

75. Luria, A.R., & Subbotsky, E.V. (1972b). Studies on the development of conscious action. Report 4. New Studies in Psychology and Physiology of Age (Novye Issledovaniya v Psikhologii i Vozrastnoi Fiziologii), 2, 28-32.

76. Luria, A.R., & Subbotsky, E.V. (1972c). Studies on the development of conscious action. Report 5. New Studies in Psychology (Novye Issledovaniya v Psikhologii), 1, 37-39.

77. Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. New York: Oxford University Press.

78. Wood, D. J., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychiatry and Psychology, 17(2), 89-100.

79. Subbotsky, E.V. (1987). Communicative styly and the genesis of personality in preschoolers. Soviet Psychology, 1987, 25, 4, 38-58.

80. Cole, M. & Levitin, C. (2006). The autobiography of Alexander Luria. A dialogue with the Making of Mind. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Ass.

81. Barkley, R. A. (1995). Linkages between attention and executive function. In G. R.Lyon & N. A. Krasnegor (Eds.), Attention, memory, and executive function. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Co.

82. Barkley, R. A., DuPaul, G. J., & Costello, A. (1993) Stimulants. In J. S. Werry & M. G. Aman (Eds.), Practitioners guide to psychoactive drugs for children and adolescents (pp. 205-237). New York: Plenum.

83. DuPaul, G. J., & Barkley, R. A. (1993). Behavioral contributions to pharmacotherapy: The utility of behavioral assessment and therapy in medication decisions for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behavior Therapy, 24, 47-65.

84. Wigal, S.B. (2009). Efficacy and safety limitations of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder pharmacotherapy in children and adults. CNS Drugs, 23, Suppl 1, 21–31.

85. Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., & Spinrad, T. L. (2006). Prosocial development. In N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Series Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (Vol. 3, pp. 646–718). New York: Wiley.

86. Milner, B. (1964). Some effects of frontal lobectomy in man. In J. M. Warren & K. Akert (Eds.), The frontal granular cortex and behavior (pp. 313–334). New York: McGraw-Hill.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.